March 30, 2021

America’s child care industry was in a precarious state even before COVID-19. But there is little question that the pandemic has exposed and exacerbated the sector’s longstanding challenges – and created new ones along the way. Though most of the nation’s providers have reopened following emergency closures mandated early in the pandemic, the ongoing fiscal solvency of the industry remains very much in doubt.

While temporary supports such as sustainability grants, subsidy enhancements, and compensation bonuses underwritten by federal relief dollars have helped bridge many providers through 2020 and early 2021, it is still too early to know the true impact of the pandemic on American child care providers, many of whom have exhausted their savings and taken on debt simply to survive to this point.

Others have not been as lucky. While likely short of the field’s most dire predictions, there is little question that many child care providers have shuttered their doors permanently as a result of COVID-19, further reducing access to a service that up to half of American families (located in “child care deserts”) already found difficult to access pre-pandemic.

The question of reduced access may be especially applicable for the nation’s low-income children, many of whom are children of color. Faced with the dual realities of potential insolvency and substantially reduced demand during a public health crisis, providers may reasonably seek to raise already high tuition rates for those who remain, potentially eliminating access for low-income and minority children.

To keep up with the rapidly evolving pandemic child care landscape, The Hunt Institute took action in early April 2020 to create the nation’s most comprehensive clearinghouse of state’s child care actions, tracking state closures and guidance, executive actions, and use of federal relief funds. That tracker continues to be updated regularly, providing valuable information to states as they develop new policies and strategies for supporting the child care industry.

Drawing from this ongoing data collection and in-person interviews conducted in February and March of 2021 with select state child care administrators, this brief summarizes our current knowledge of equity issues within state child care systems, including access, affordability, and efforts to support the child care workforce.

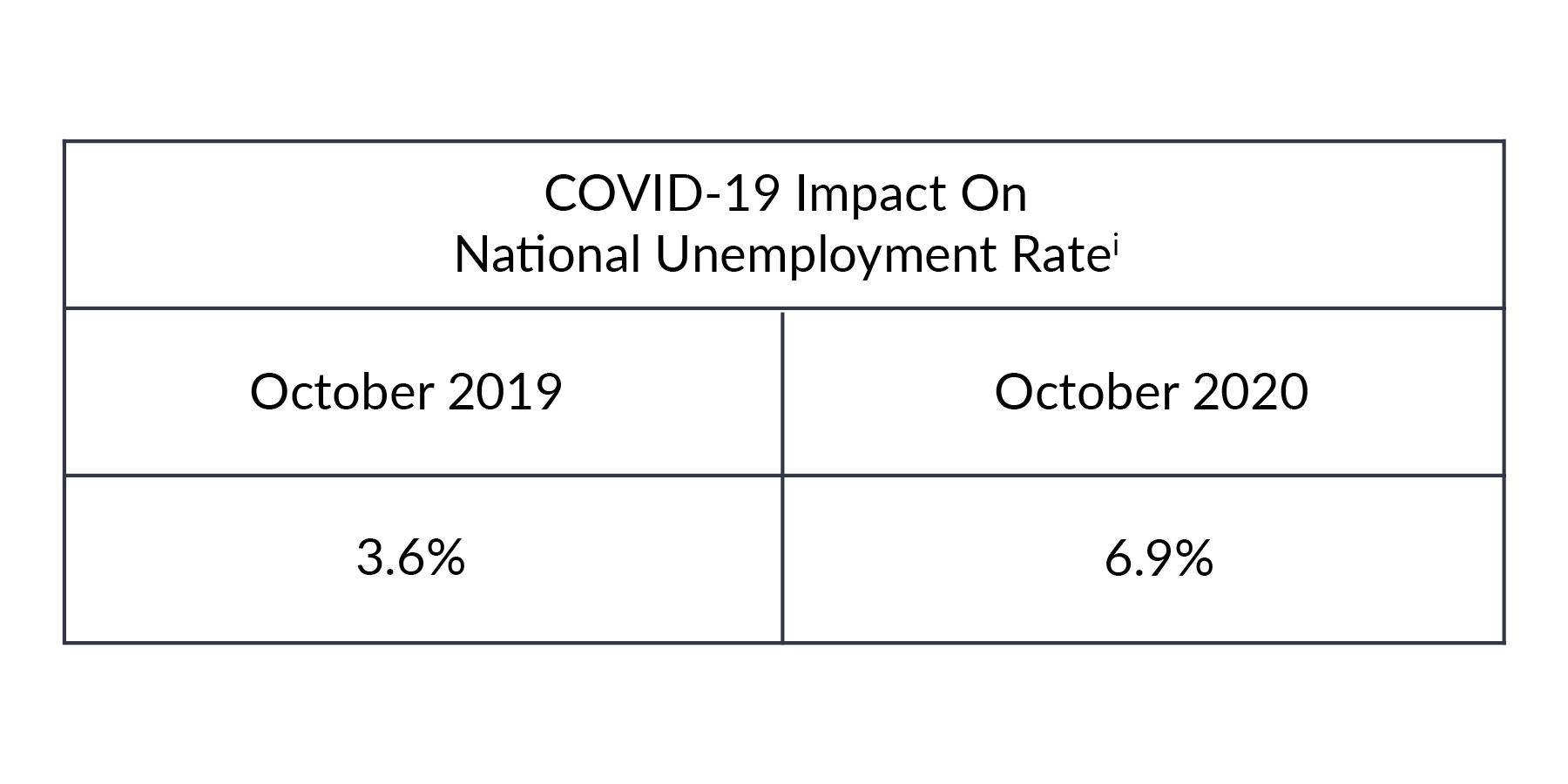

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly changed the nation’s workforce landscape, dealing a severe blow to state economies, businesses, and workers. A recent comparison shows a dramatic increase in unemployment rates:

The pandemic has also caused dramatic changes in the landscape for child care and early education programs in the United States. Already operating as a fragile system, child care programs have experienced financial turmoil, mandated closures, fluctuating and unpredictable demand for child care, costly new health and safety regulations, and shifts in school district plans for K-12 virtual learning. A June 2020 survey conducted by the National Association for the Education of Young Children estimated that without assistance, two in five child care programs would close permanently.

In addition, the pandemic brought into focus the realities of the nation’s early childhood workforce, comprised largely of women of color: poverty-level wages, lack of access to health insurance, and no paid sick leave. As a result, many educators have been forced to choose between a paycheck or their personal and/or family health and safety.

Across our interviews, state child care administrators highlighted the impact COVID-19 has had on the child care and early childhood system, amplifying the inequities that existed prior to the pandemic.

Most state administrators interviewed do not collect or analyze data based on demographics and typically only have data on children receiving subsidies within participating centers. From the data available, states saw variance in enrollment demographics – some states saw large decreases in subsidy enrollment, others saw no significant decline. One state administrator felt families receiving subsidy did not have the luxury to stay home or not work, therefore subsidy enrollment did not decrease. Another expressed a belief that families of color were less likely to send children to child care due to concerns about health and safety. Other states mentioned many families have begun using unlicensed child care such as friend, family, and neighbor care.

Wage and Benefit Gap of the Early Childhood Workforce

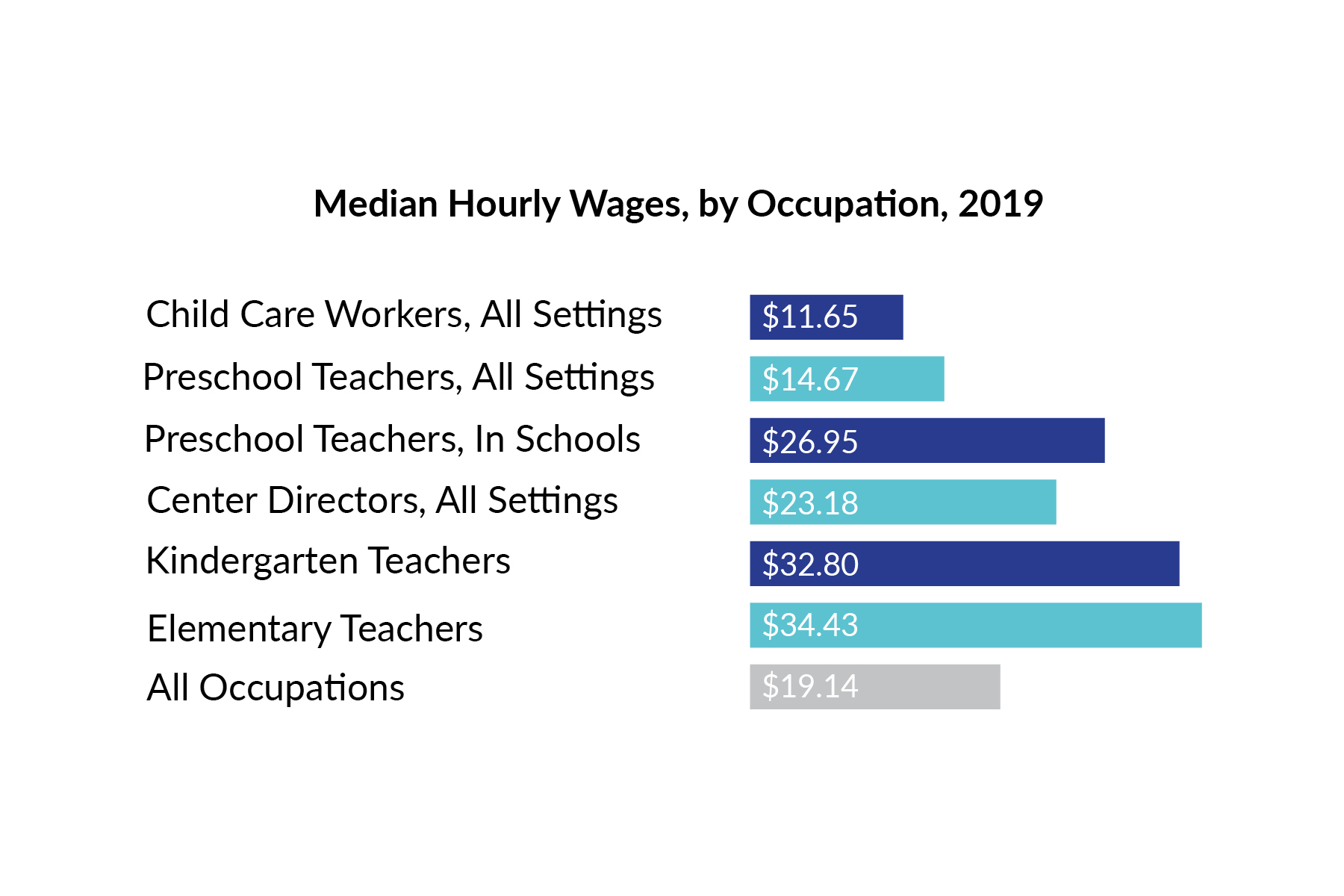

The early childhood workforce plays an important role in the economy by allowing parents of young children to pursue employment outside the home and by providing children stimulating and nurturing environments where they can learn and grow. In recent years, families have increasingly relied on child care because spending more time at work has become an economic necessity for many. Despite the critical nature of the work, the early childhood workforce is among the country’s lowest paid. Further, these professionals seldom receive job-based benefits such as health insurance and pensions. As with any other industry or occupation, paying decent wages and providing necessary benefits is essential to attract and retain the best workers.

Low wages for the early childhood workforce are particularly evident when comparing to the salaries of kindergarten teachers. For example, despite having equivalent education, public pre-K teachers with bachelor’s degrees working within a public school earn roughly 81 percent of the salary of similarly educated kindergarten teachers. Public pre-K teachers with bachelor’s degrees working in community-based settings fare worse, earning only 64 percent of kindergarten teachers’ salaries, and preschool teachers who do not work in public pre-K settings earn only 55 percent of what comparably educated kindergarten teachers earn.ii

Source: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (2021), Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2020

Low compensation negatively influences the ability of early childhood programs to attract and retain experienced teachers and caregivers, resulting in high turnover rates. These high turnover rates can negatively affect classroom instruction, teacher-parent and teacher-child relationships, program quality, and workplace environments.

Estimates show that, from 2014 to 2016, more than half of the early childhood workforce was enrolled in some type of government assistance program, compared to 21 percent of the overall national workforce. Financial insecurity undermines basic psychological needs and is associated with higher levels of stress and depression. Additionally, increased levels of stress and depression in early childhood teachers have been linked to negative learning environments.iii

States have been implementing strategies in an effort to address this issue. Such strategies include direct wage supplements tied to education, professional development scholarships with compensation incentives, tax credits, and wage parity requirements built into state-funded pre-K standards or within individual state’s Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS). Some states and cities are also targeting efforts to increase minimum wage to address the problem. Most state efforts have been aimed at providing financial relief, but not changes to the actual wages. The most direct means to improve compensation for early educators is to articulate compensation standards, make them mandatory, and provide both system reform and sufficient public funding to meet those standards.

The issue of workforce compensation, including wages and benefits, was prominent in conversations with state administrators.

Kentucky

Due to extended child care provider closures, the primary concern of the Kentucky Division of Child Care (DCC) during the COVID-19 pandemic was to preserve remaining child care capacity. As such, the state utilized part of the federal CARES Act to provide financial relief to child care centers through a variety of innovative approaches. One such approach, titled the “Hero Bonus,” provided a $1500 stipend to more than 800 child care providers working in Limited Duration (Emergency) Child Care. In recognizing the wage and benefit disparities experienced across the child care industry (only 16-17% of child care programs in Kentucky offer health care), the state took an innovative approach to a solution by conducting outreach to all 2,200 child care programs to help employees enroll in the state Medicaid system (Kentucky has expanded coverage to low-income adults). As of September 2020, Kentucky has enrolled 1,523,066 individuals in Medicaid and CHIP (an increase of 151 percent since the first open enrollment and related Medicaid program changes in October 2013).

Connecticut

In the early stages of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, OEC launched a series of supports, CTCARES Programs, including a care package focused on licensed family child care programs, CTCARES for Family Child Care. This innovative approach established contracts with trusted community organizations across the state to operate staffed Family Child Care Networks offering access to supports like child care health and early childhood behavioral health consultants. Participating programs also gain access to business coaching, administrative supports, and membership to the National Association for Family Child Care (which operates a quality accreditation program for home-based care), among other features. One of the greatest strengths of the Family Child Care Networks is their location in the geographic areas they serve, helping to develop relationship with local providers and families, and better meet the unique needs of their community.

The OEC is planning to use the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index as a consideration in how it implements ARP funding coming for child care. During the pandemic, OEC noted that children living in areas of the state with higher Social Vulnerability Index ratings returned to child care at a slower rate compared to other areas.

Delaware

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Delaware Division of Social Services (DSS) used its 2018 Delaware Local Child Care Market Rate Survey results to set the provider reimbursement rates for child care services subsidized by the State. Child care reimbursement rates were based on the providers geographical location, the ages of the children served, and the hours of care. DSS established the child care reimbursement rates to ensure that low-income families receiving child care subsidy have equal access to early education and care.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and to support child care programs stay solvent, Delaware has implemented an enhanced child care reimbursement rate.

A 2021 Delaware Local Child Care Market Rate Survey was completed, finding a statewide 3 percent increase in child care market rates was advisable. Market rates are prices providers charge parents for the care of children. Similar to other states, the Delaware Division of Social Services planned to utilize the information obtained from the survey to inform state decisions regarding reimbursement rates for child care services purchased by the state (the child care subsidy system).

Recognizing the increased need for child care services, and the pandemic hardships faced by families and child care providers, DSS, in consultation with the Department of Education, have conducted a Narrow Cost Analysis to clearly understand the actual cost accrued by providers to care for children. This data will be utilized, in conjunction with the Market Rate Survey, to provide a more adequate reimbursement to providers and families based on the level of quality.

Family child care programs, or child care provided in homes, has been a quality option for families and unique component of state child care systems long before the COVID-19 crisis. According to the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, close to one million family child care providers were in operation, caring for over three million children across the United States.

This program setting is a family choice for a multitude of reasons. It is often the preferred choice for parents of infants and toddlers or children needing individualized care. It is also an opportunity to have siblings in the same care setting, an opportunity to identify caregivers with the same cultural values and spoken language as in the home. Likewise, family child care programs may be the only choice for parents working non-traditional hours.

Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, family child care programs were more likely to remain open than center-based care. The University of Oregon’s Rapid Assessment of Pandemic Impact on Early Childhood Development research shows that while use of center-based care fell substantially and has not fully recovered, use of home-based care (including family, friend and neighbor care) dipped less and has returned to pre-pandemic levels. Surveys by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) show that 18 percent of child care centers remain closed, compared to 8 percent of family child care homes.

Although a lower percentage of family child care programs remain closed, many are operating at a loss and under capacity. Additionally, this program setting faces unique challenges. One such is the lack of engagement or inclusion with the state child care system, as family child care programs rarely participate in the state child care licensing process, child care subsidy program, or quality rating improvement systems. It is important to note that family child care (FCC) is regulated differently depending on state rules, meaning that a family child care program considered legally exempt from licensure in one state may be required to apply for a state license in order to care for even one unrelated child in another. As states seek to recover and rebuild with equity post COVID-19 pandemic, it will be critical to integrate family child care programs into their plans.

Family child care programs also experience the challenge of equity through resources and access. These programs are disproportionately used by families with lower-incomes and parents who speak English as a second language. Sole owner-operator family child care programs require their owners to be the financial manager, director, teacher, parent engagement specialist, cook, janitor and more. Yet, these programs, in most states, are typically reimbursed less than center based child care programs in the state child care subsidy system. More equitable payment rates, systems of support, and strategies to support the business stability of family child care programs are possible with new federal resources. For instance, staffed Family Child Care Networks are one way states can build an infrastructure to provide family child care programs an opportunity to share overhead costs and access services together.

Survey Trends

State’s Plans for New COVID Relief Funds

Although many of the states have yet to finalize their plans for relief dollars, each state administrator expressed an intent to use the funding to build a better and more equitable statewide early childhood systems. Thoughtful approaches are being taken to determine the most effective strategies to accomplish such, as many state administrators reflected on the limited nature of this relief funding.

As in the initial round of funding, state administrators noted a plan to provide operational grants to child care providers to support reopening and fiscal solvency, enhance health and safety practices to meet Centers for Disease Control guidance, and provide direct payments to child care staff. In addition, states are continuing to offer enhanced child care reimbursement rates, basing payments on enrollment, and waiving copayments for families.

Innovative cross-state approaches were also noted, including an approach in which several states made a regional decision to create a singular plan, allocating funding through operational awards that encourage child care programs to address workforce compensation. Other innovate approaches include states using their funding allocations to support family child care pilot programs. Others are addressing learning loss by extending the school year and school day through summer programming, and enhancing transition activities to support kindergarten entry for children and families who were not engaged in early childhood programs over the past year.

Equity through Access Considerations

Although states are reporting the reopening of child care programs, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a detrimental impact on the child care industry, with a significant number of programs permanently closing – decreasing access to care for families returning to work. States are providing supports by prioritizing funding for child care programs to reopen (i.e., start-up grants), expanding access to the child care subsidy program, increasing market rate reimbursement strategies, and continuing policies to streamline processes for parents and providers. Innovative examples of these supports include states increasing subsidy eligibility for families, allowing a greater number to access quality child care. In addition, states reported simplifying the child care licensing process, often transferring portions online to ease the process for child care providers.

One state adapted their quality rating improvement process to be more equitable by shifting to an internal assessment process for centers. This allows for a continuous quality improvement process uniquely designed to each individual child care program, while removing barriers of the high stakes assessments found in the traditional Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS).

These innovative changes were made due to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the positive impact to improving access for providers and families was substantial. As a result, several states are adopting, on a permanent basis, the innovative solutions made to their child care licensing and subsidy system that arose during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Each of the states interviewed had suggestions for how to support states as they develop policies related to equity and COVID-19:

___________

[i] US Bureau of Labor Statistics

[ii] Whitebook, M., Phillips, D., & Howes, C. (2014). Worthy work, STILL unlivable wages: The early childhood workforce 25 years after the National Child Care Staffing Study. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from https://cscce.berkeley.edu/files/2014/ReportFINAL.pdf.

[iii] Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2004). Self-reported depression in nonfamilial caregivers: Prevalence and associations with caregiver behavior in childcare settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19, 297–318