As the coronavirus pandemic has led to a massive wave of school closures and virtual learning, many students have experienced significant learning loss. The coronavirus pandemic has taken existing academic achievement differences between students and exacerbated them, with one stark example being the digital divide that exists between students. The World Economic Forum estimates that over 55 million K-12 students were affected by school closures caused by the pandemic. While some schools have reopened for traditional in-person learning, many schools have opted for full remote instruction or adopted a hybrid model. As many schools remain closed for in-person instruction, educators and policymakers have attempted to protect students from chronic absenteeism, which has disproportionately affected Black, Brown, and low-income students who lack the ability to stay virtually connected in their online learning as they lack the technology and resources needed for online learning.

While not a new predicament, the coronavirus school closures have further exposed existing disparities in both resources and quality of student education between low-income students and their higher income peers, particularly low-income students of color. Some of the biggest inequalities exist within the large tech divide that contributes to the “homework gap”—students lacking the connectivity they need to complete schoolwork at home— that is growing as many lower-income and rural students have trouble keeping up with online assignments because of their lack of internet access.

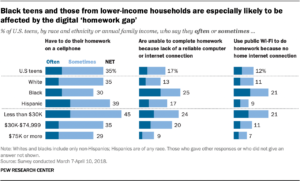

The digital divide has been undermining the academic success of low-income students since well before the pandemic introduced a massive wave of remote instruction. Evidence finds that as many as one-in-four teens in households with an annual income under $30,000 lack access to a home computer. Research finds that the “homework gap” is more pronounced for Black, Hispanic, and lower-income households. Differences are also found when examining geographic location. 65% of students attending suburban schools were used to using the internet for homework almost every day, compared to 44% of students who attended schools in rural communities. However, limited broadband access is not solely a rural issue. Reports by the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia found that 40 percent of students who lack internet access live in urban areas.

Most teachers (roughly 75 percent) teach students that lack access to technological tools, and lack of access to high-speed internet is a serious barrier to effective implementation of remote learning. Some children even report having to do schoolwork on their cellphone or relying on public Wi-Fi from libraries and restaurants. However, another concern lies within a family’s ability to pay internet or cellphone bills during the current economic instability as lower income families have reported to be worried about these types of bills.

An equity crisis is clear as the disproportionate share of students who lack access to reliable internet connection and technology are Black, Hispanic, live in rural areas, or come from low-income households. Without access to the tools and resources required to successfully engage and participate in online learning, many students will fall behind academically, further widening the pre-existing achievement gap. As COVID-19 continues to require more schools to adopt online learning, vulnerable students will likely fall behind; therefore, it is imperative that educators and policymakers prioritize the lack of equitable digital inclusion of all students.

With less than one in three school districts including the distribution of mobile broadband hotspots as part of their initial COVID-19 response plans, educators worried about vulnerable students falling behind their more resourced peers. Fortunately, many states and districts have taken steps to combat the digital divide and provide students with the resources required to succeed in online learning.

Fort Worth, Texas: As the fifth largest school district in Texas, the Fort Worth Independent School district officials were largely concerned with providing their students the resources to transition to online learning. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Fort Worth ISD spent $13 million to purchase 63,000 Google Chromebooks, tablets, and 21,000 mobile Wi-Fi hotspots to distribute to students. However, district officials only saw this as a temporary fix.

Currently, Fort Worth ISD and the city of Fort Worth plan to establish free public Wi-Fi in underserved communities. Further, this partnership aims to work towards providing complimentary plans to areas of the city with low rates of broadband access. This proposal attempts to establish permanent infrastructure in high poverty parts of the district, not only to combat the current online learning crisis, but to enrich student learning and perhaps combat summer learning losses.

Washington D.C.: Mayor Muriel Bowser has launched a $3.3 million Internet for All initiative to connect eligible D.C. traditional and charter public school students in need of at home internet for the 2020-2021 school year. This initiative aims to provide 25,000 low-income students with free internet access, with funds allocated by the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). OSSE prioritizes SNAP and TANF eligible families who lack reliable internet connectivity.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Through PHLConnectEd, the city of Philadelphia aims to address digital access inequities which have been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. This program provides eligible K-12 households with free wired, reliable internet from Comcast or a high-speed mobile hotspot for families who are housing insecure. The city aimed to connect 35,000 low-income students for the 2020-2021 school year, using collected data that studied how residents use and benefit from the internet, allowing the city to better target students and families who need access support.

Datacasting: Datacasting or data broadcasting is a public safety feature being repurposed in hopes of connecting rural students with reliable internet access during online learning. This new technology bypasses the need for a cellular network or internet service and uses television broadcast signals to distribute information to wireless enabled devices such as smartphones, tablets, or Chromebooks. The Fairfield County School District in South Carolina is among three districts piloting the program and aims to serve 5,000 students across the state within the first year. Other states such as Indiana and Pennsylvania are also investing in this technology and aim to use it by the end of 2020.

Since the pandemic led to the sudden closure of many schools across the nation, districts and educators have made many efforts to provide students with learning opportunities. However, despite dedicated efforts, the drastic transition to online learning has highlighted the longstanding equity issues within the digital divide. Therefore, states and districts should aim to combat these technological inequities which hinder the learning of vulnerable student populations.

Look Beyond Temporary Solutions: The digital divide has undermined the academic success of students from low-income families far before the pandemic led to many schools transitioning to online learning. Former President Bill Clinton had even created a proposal to help bridge the growing divide. However, it is clear that the digital divide is far from closed and disproportionately impacts students of color and those from low-income and rural backgrounds during online instruction. Therefore, policymakers should aim to promote a solution that looks beyond the current crisis and work to permanently close the digital divide. Investing in data collecting initiatives is a first step to addressing the hidden dimensions of the divide.

Adopt Local Partnerships: As a multifaceted issue, the technology divide can be better addressed when local and state governments and the private sector work together. Using past successful partnerships as a guide, state leaders should consider partnering with low-income communities to collaborate and bring technology to these communities.

Advocate for Federal Funding: State policymakers should consider advocating for more federal funding needed to implement effective and sustainable changes in these communities. While Congress provided the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act in March, this investment has fallen short in ending the technological divide impacting vulnerable student populations. With education advocacy groups estimating a need for aid ranging from $100 billion to about $250 billion, federal funding is crucial to address the current disparities that exist in state funding.