Last spring, in response to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, schools swiftly closed their doors to traditional in-person learning and transitioned to online instruction. Almost a year later, many education stakeholders and policymakers continue to grapple with how to safely reopen in-person schooling as new vaccine rollout begins.

Federal and state vaccine rollout plans are well underway across the United States. As of this brief’s publication, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have reported that an estimated 32.9 million people have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, with about 9.8 million of those individuals having received the additional dose. Most, if not all, states are struggling with the implementation of effective and equitable vaccination plans; vaccine data finds just 3.5% of the Latino population and 4.5% of the Black population in America have received the coronavirus vaccine compared with 9.1% of the white population and 8.6% of the Asian population in America. This challenge is at least partially due to communities of color holding a justifiably inherent mistrust of government-funded vaccines that stems from the history of harm inflicted upon their communities by government-funded research and medical studies. Therefore, these disparities are especially critical to understand and address as Black and Latino communities have faced disproportionate harm throughout the pandemic.

Many students have returned to at least some form of in-person instruction, and at least five states now require in-person instruction to be available in all or some grades. However, many students, specifically those in large city districts, continue in full remote learning for fear of spreading the virus. When COVID-19 first emerged, pediatricians warned caregivers against in-person schooling and more than 50 million American students finished the 2019-2020 school year through a variety of remote learning and home schooling programs.

Pfizer, the leading coronavirus vaccine research organization, has fully enrolled its COVID-19 vaccine trial in children ages 12 to 15. The benefits of vaccination go beyond the physical protection it provides children, including protection against rare complications of COVID-19 and post-infectious conditions. Vaccination also offers reassurance to school employees and protects others by reducing spread.

School disruption has occurred in many past health crises. As schools plan to reopen for in-person instruction and the United States’ plan for vaccine distribution continues, education stakeholders can evaluate initiatives developed from past health crises that affected school-age children. Below, we highlight past schooling responses during global health crises and best practices for safe student learning.

During the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic in the United States, most cities aimed to implement community mitigation strategies, such as school closures. While a priority before the influenza pandemic, improving school facilities and health conditions for students became of large concern for the United States government as it attempted to combat the spread of influenza. At that time, schooling was often conducted in unsanitary and poorly ventilated buildings. School districts, much like today, debated whether to keep schools open or to close schools to prevent widespread infection. Similar to the swift response of school shutdowns in spring 2020, most state and local governments made the decision to close schools in 1918.

Two of America’s largest cities in 1918, New York City and Chicago, kept their schools open and attempted to enhance medical surveillance of students. Health commissioners believed that students would be safer under supervision of school officials than in their unregulated homes. In 1918, the New York City Health Commissioner, Royal Copeland, highlighted the importance of well-equipped school nurses. Copeland believed that schools with trained nurses provided students with a degree of safety and the opportunity to learn in addition to educating parents on the demands of public health. Some states instituted statewide school closure mandates such as in New Jersey and Louisiana. In North Carolina, policymakers advised school leaders to consider closing schools if influenza became prevalent in their communities.

In analyzing the responses to the 1918 pandemic, research showed that cities who implemented social distancing, quarantine, isolation, and school closures fared better. Further, high absenteeism in schools that remained open became a large problem. Chicago public health officials reported massive “flu phobia” amongst parents. This “flu phobia” also often developed into a fear of bringing their children to hospitals to receive medical treatment due to close proximity to those infected.

During the 2009 H1N1 influenza epidemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considered school closures as a measure for infection prevention.

Ultimately, the CDC recommended that the primary response of caregivers of school-aged children should be to keep feverish children home, allowing them to return to school 24 hours after the resolution of fever. Further, the CDC recommended that the primary response of schools should be to separate ill students and staff and promote extensive hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette.

The CDC also recommended that school districts with a high population of vulnerable students likely to develop severe influenza complications consider closing and suggested that if H1N1 developed deep severity, school dismissal be considered as a general option by affected school districts. As a result, roughly 700 schools closed when the H1N1 flu first struck in April and May of 2009.

Analysis of previous public heath efforts and vaccination programs finds that uptake of children’s vaccines was largely dependent on caregivers’ perceptions and attitudes. The main motivators for vaccine acceptance by caregivers were the professional influence of a pediatrician and low medical cost. Caregiver trust and communication with qualified providers also heavily influenced immunization decisions.

As the COVID-19 vaccine continues to be distributed throughout the United States, many parents are wondering if the vaccine will be mandated by the government or schools. While Pfizer and Moderna, two of the three most promising drug makers of the vaccine, have started testing on children 12 and older, it will likely be many more months before children can get vaccinated.

Experts have estimated that roughly 70 to 90 percent of the population should be immunized against the coronavirus to reach herd immunity. To achieve this goal, children will also likely need to be vaccinated. Dr. Emily Erbelding, an infectious disease physician at the National Institutes of Health, states that, “not all adults can get the vaccine because there’s some reluctance, or there’s maybe even some vulnerable immune systems that don’t respond.” Therefore, Dr. Erbelding believes children will have to be included in vaccinations to achieve herd immunity, raising the importance of immunization with children of racial and ethnic populations hit hardest by the pandemic. Individuals younger than 21 account for a quarter of the population in the United States, but have made up less than one percent of deaths from coronavirus. However, Black, Latino, and American Indian individuals are disproportionately represented in the number of deaths. While these groups represent roughly 41% of the under-21 population in the United States, Black, Latino, and American Indian individuals account for more than 75% of under-21 COVID-19 deaths.

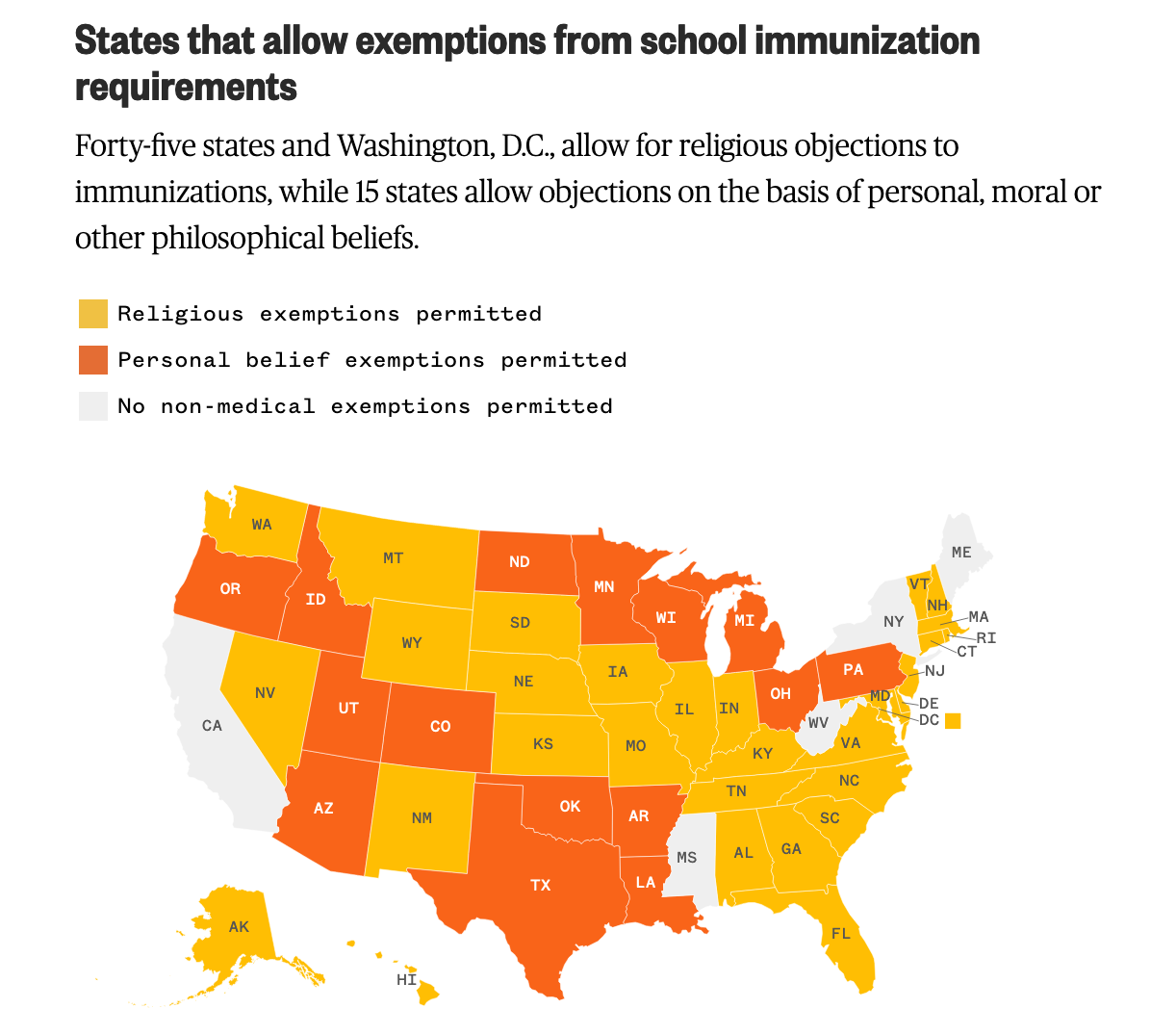

When vaccines for children become available, states have the power to mandate them, per the 1905 Supreme Court Case, Jacobson v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. All states have current vaccine requirements for diseases such as tetanus and polio in order for children to attend school, yet many states provide the opportunity for families to opt out.

As the coronavirus vaccine for children continues to be developed, states will grapple with how to best approach vaccinations in an effort to achieve herd immunity and provide students with a safe and high-quality learning environment.

Invest in school sanitation and full-time school based medical staff | As schools return to traditional in-person learning, new sanitation requirements will need to be enforced to mitigate the risk of infection. Additional resources are required such as PPE, sanitization equipment, and relevant information to address non-COVID related illnesses. When school nurses were first introduced, they were found to have a significant positive impact on the health of students. Research finds that school nurses help address a variety of mental and physical health needs of students and cut chronic absenteeism by almost half. However, there is a nationwide shortage of school nurses, with only three out of five schools employing a full-time nurse. Policymakers should consider initiatives to attract and support school nurses to distribute vaccines and address other student health-related needs, including mental health.

Communicate clearly with parents, caregivers, and guardians | Previous health efforts and vaccination programs have highlighted the importance of caregiver support and perception with regard to the uptake of student vaccination. For children under the age of 18, caregivers are often the decision makers regarding their child’s vaccinations. Lack of knowledge and high costs are often associated with low confidence in vaccinations; therefore, policymakers and education stakeholders should work to provide all caregivers with the appropriate knowledge and resources to make an informed decision regarding their child’s vaccination.