February 12, 2021

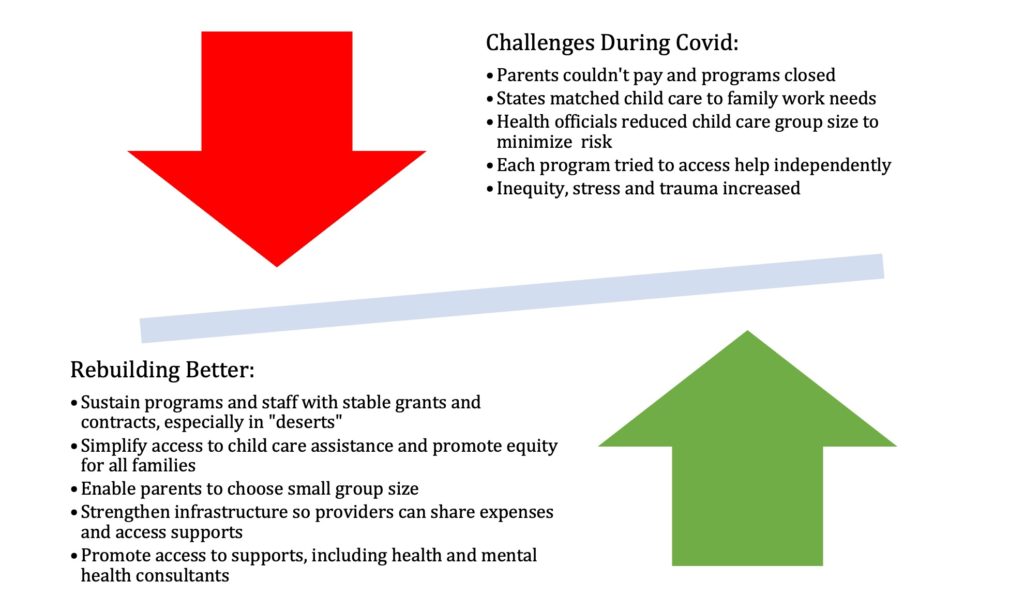

State leaders know that child care is an essential support to keep parents working, communities thriving, and their economies humming. High quality care also promotes school readiness. But this essential industry is currently reeling from the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic downturn that has accompanied it.

Prior to the pandemic, 88 percent of two parent families and 83 percent of single parent families working full time used non-parental child care for children under age five. By May 2020, the majority of child care centers and about a third of home-based child care businesses were closed due to either a gubernatorial order or lack of demand.

While most child care programs operate as businesses, many do so on profit margins lower than one percent. And with pandemic-related closure and limits on classroom group sizes driving down revenues, more than half of child care centers surveyed in December 2020 said they are losing money every day they serve children. National data suggests that many child care owners had difficulty accessing the federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). This was especially true of small business owners operating child care programs within their homes.

Now polls are showing parents want to be sure their children’s health can be protected before they can feel good about leaving home for work and putting their child in non-parental care. Bold actions are needed to prevent widespread permanent closures and rebuild child care stronger and better in our new reality.

State leaders have been at the forefront of this pandemic, including in making new policies and programs to support child care programs. Congressional approval of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act in March provided $3.5 billion and additional flexibility to states in how the funds could be used on an emergency basis as part of the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) program. The Hunt Institute’s COVID-19 Child Care Policy Tracker has cataloged these policy changes, from closure orders to CARES Act usage and reopening plans. Although these changes were born out of crisis, many address longstanding weaknesses in how the market for child care has developed in the country and provide examples of how to strengthen an essential service millions of parents rely on to nurture and educate their children while they work.

This brief highlights policy shifts that would help to ensure families have equitable access to the quality care they need in a post COVID-19 world. Now that Congress approved a second relief package that included an additional $10 billion for CCDBG, while preserving flexibility for states to make key decisions on how best to implement relief measures, state leaders have an opportunity to continue or re-implement changes.

Before the crisis, families paid two out of three dollars spent for early care and education — the Economic Policy Institute calculated that $42 billion was spent by families out of the total $64 billion spent privately and publicly for this essential service. This crisis showed how unstable that financing system made child care programs on which working families rely. State leaders have an opportunity to communicate to the new Administration and Congress how important a stronger, well-financed child care system is for economic recovery and addressing inequity in their states. and the experiences of state early care and education leaders can help inform national leaders about how our nation’s children get back on track for school readiness and healthy development.

Stabilize and sustain child care programs with direct funding based on the number of children in a community who need child care, and not tied to what parents can afford.

Challenges | Unlike public schools and Head Start, which are underwritten by stable, ongoing revenue sources (state funding formulas and grants) and thus still paying staff salaries, child care programs are laying off their employees in large numbers as they rely primarily on parent fees. Treating child care like a public good would mean awarding foundational grants/contracts to programs or communities based on the number of children who need care, where they can be served, and the actual cost of operating at basic levels of health, safety and quality. Although an extreme example, massive COVID-related unemployment wiped out many parents’ ability to pay for care and decimated child care’s longstanding business model, which depends on full enrollment to sustain itself. Fixed costs – like rent, utilities, early educator salaries, and benefits do not change when children cannot attend or family income dips.

Ideas for the Future | With the added flexibility of the CARES Act, states were able to quickly change how they distributed child care funding to sustain child care providers directly and replace what parents could not pay. They were allowed to use the funding statewide, without regard to whether the provider was already part of the state child care assistance program operated with federal CCDBG funds. States used data on essential workers and the hours of work to inform decisions. With additional federal resources, states could continue to make key policy changes like:

Note: The 46 states that received federal planning grants through the Preschool Development Grants Birth to Five for 2018-2019 already conducted needs assessments as a condition of that grant and likely have identified the areas of the state and populations of children that were underserved prior to the pandemic. Several additional states and territories are in the planning process currently. State leaders can use that data as a starting point to allocate resources to re-build stronger.

Simplify access to child care assistance and promote equity for all families.

Challenges | Helping essential workers to find care quickly that met their work hours and children’s needs meant states waived steps that had previously been built into state child care assistance programs under CCDBG that make families wait to know if they qualify for assistance. Grocery clerks, nurses, and EMTs went through the same simplified process. Child development experts have long argued that it would be beneficial to de-link child care assistance from the hours and seasonal nature of jobs for many lower income families. Meaningful attachment and relationships between young children and their child care givers are key to positive early learning and development, and the reality is that parents who earn lower incomes – as well as health care workers – are often subject to their employers’ demands for shift work, seasonal changes in demand, and other factors.

Ideas for the Future | The CARES Act allowed states to bypass complicated means testing processes and focus on linking families to what they needed, because it said that essential workers could receive child care regardless of income. All parents could benefit from this kind of convenience. States took swift actions to:

Help parents find and afford child care in small groups that can follow social distancing rules.

Challenges | The recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to reduce the chance of transmission of disease when COVID-19 is possible in the community call for groups no bigger than 10. Currently, state licensing rules vary widely. For example, group size limitations set by states for toddler care range from 8 to 20, and for three-year-olds from 14 to 30 children in a group. Although this variation exists, there are expert recommendations for group size and other aspects of child care that are promulgated by the American Academy of Pediatrics that are typically lower than what state rules say. According to review of state rules by The Hunt Institute, 25 states set new requirements for open child care programs to have 10 or fewer in a group. A national Care.com survey found that 63 percent of parents who had relied on child care now were somewhat or very uncomfortable about sending their children back right away, and 35 percent were considering in-home care.

Ideas for the Future | Given the gap between existing state licensing rules and expert recommended staff:child ratios and group sizes, states may want to review whether their licensing rules should be altered until a vaccine is available and beyond. States learned during the pandemic to:

Strengthen child care infrastructure by building family child care networks and shared services alliances at the community level.

Challenges | The history of how child care programs have developed has been haphazard and based on the private market – with the exception of the federal Head Start and Early Head Start programs, and the move toward increasing access to public prekindergarten. Programs are mostly operated by small business owners or larger chains. About half of the disproportionately women of color who are in the child care field make wages low enough to quality for food stamps and other social service programs, since the average hourly wage for an early educator is $12.12 an hour. Analysis from a business perspective has convinced some leaders in the field to say small programs cannot survive in the current system without working together to share their expenses. Small business family child care providers offer parents small group care out of their home, and surveys by the National Association for Family Child Care showed that two-thirds stayed open to serve children and families despite few accessing relief programs or hazard pay available to those serving essential workers. As independent operators, family child care providers can feel isolated from supports in their communities and need to be have supports to access current pandemic information, health and safety supplies, and public and private relief programs.

Ideas for the Future | States have piloted networks and shared services alliances to cut down on the overhead costs, share back office functions (accounting, food purchasing, payroll), hire substitutes for when teachers are sick, manage access to child care assistance, and engage in peer learning. During the crisis, government and philanthropy have had to step in to fund and arrange for needed supplies as well as help programs apply for federal funds that demanded tax and accounting records. Networks and alliances are ways to strengthen capacity and share costs long-term.

Ensure equitable access to services to help children, families, and child care providers deal with trauma and stress.

The pandemic has raised anxiety and exposed fault lines that often map to racial and economic inequity that pre-existed this crisis. According to the Centers for Disease Control, African and Hispanic Americans who contract the COVID-19 virus are more likely to die than Caucasian or Asian Americans, potentially due to: working in essential service jobs, lack of health insurance and care, and living in more crowded conditions due to lower incomes and racial and ethnic segregation. Children living in households that have experienced loss of income, increased food insecurity, and parental stress are likely to have some negative pressures on their early childhood development. All children are likely to have lost access to their peers and normal routines with adult caregivers. Children may develop high anxiety, challenging behaviors, and delays in development and learning that can be identified during and after the pandemic. When they return to child care, it may be very different than what they experienced before.

Ideas for the Future |

State leaders have been working overtime to address the immediate needs to sustain child care during the pandemic and made innovative changes quickly. Federal CARES Act funding and flexibility helped sustain those changes, but as those dollars ran out some states had to roll back these innovations. Some states have used other federal relief funds for child care. For example, Illinois is using Coronavirus Urgent Remediation Emergency (CURE) Funds for grants to child care to replace lost business income during the pandemic. Communities have also voted in referenda across the country to raise revenue through local taxation strategies. At the end of 2020, Congress appropriated an additional $10 billion for CCDBG. Debate continues as to how to fully address the challenges facing the child care industry – analysis released in May estimated that $9.6 billion is needed every month to keep the child care industry open and pay staff despite a major short-term decline in demand. At the federal level, different proposals were considered through 2020, and the new Biden Administration included $40 billion more in its January 2021 pandemic recovery proposal. During this national crisis, federal, state, and local government and business leaders would be wise to take this opportunity to come together to build a stronger and better child care system that makes the burden of paying for care more equitable for the sake of our nation’s future.