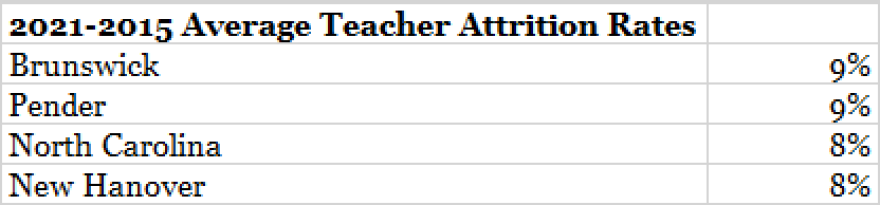

In the Cape Fear region, Brunswick County Schools had the highest teacher attrition rate at 10%, followed by New Hanover at 9% – both over the state average of 8%. Pender County had a lower rate of 7%.

Overall, the Southeast Region, which includes New Hanover, Brunswick, and Pender had the highest attrition rate at 9.2%. (The Southeast Region also includes Duplin, Onslow, Wayne, Greene, Lenoir, Craven, Jones, Pamlico, and Carteret counties.)

North Carolina education leaders, like State Superintendent Catherine Truitt, praised those numbers, saying it’s a stable rate even after the first year of the pandemic.

According to a March press release from DPI, Truitt said, “To be sure, attrition from the state’s teacher corps remains a concern and a challenge that we must address more aggressively, but the numbers for the 2020-21 school year show that the state didn’t see a big surge in teachers leaving the classroom, at least in the first 12 months of the pandemic. We’ll be assessing the impact of the second year of the pandemic when we’re able to analyze data from the 2021-22 school year.”

Historically, though, New Hanover County is tied with the state average rate of 8%, according to attrition rates compiled from 2015-2021.

A majority of teachers cite “personal reasons” as their main reasons for leaving, followed by “reasons beyond the district’s control,” “other reasons,” and “initiated by the district.”

But according to WHQR’s analysis of monthly personnel reports, from April 1, 2021, up until March 1, 2022, New Hanover County Schools have lost 183 teachers (this analysis didn’t include teaching assistants) — a rate of about 11%. About 81% of those are teachers who resigned, and the remaining percentage are ones who retired. And those figures aren’t reflected in the state’s current report.

Dr. Chris Barnes is the assistant superintendent of human resources for the district.

“For the last four months that I’ve been tracking it, we have doubled our hires from our resignations and retirements. So if you look at those numbers, we have brought in twice what we’ve lost. But how do we turn off that spigot of losing people mid-year?” said Barnes.

Teachers talk about why they’ve left

Kim Roth was one of those teachers who left mid-year. She taught middle school for 27 years. She left Trask Middle School in January, only a year and seven months from retirement. She now works for PPD.

She recalls the exact moment when she decided to leave. Kim was called into a parent-teacher conference over a student accusing her of singling him out over enforcing the mask policy.

“And they [the parents] were really angry, [they said] he was the only one who I had asked to pull his mask up, and I sat in there, being yelled at in front of the child with an administrator in there that wasn’t doing anything to stop it. And I thought this is it. I’m leaving. I’m not making it another two years. I’m gone,” said Roth.

Blair Deen, a 13-year veteran, also left mid-year. She taught career and technical education classes — and last year, she earned her National Board Certification and was named Hoggard’s Teacher of the Year. She’s now the facilities design coordinator for Novant Health.

“One of the biggest reasons, one of the biggest things was the big lack of student accountability these days.[…] We are expected to hold our students to high expectations yet, they put in place these policies of a 50% on an assignment for doing absolutely nothing, or 50% on a test when you didn’t even take it,” said Deen.

Kim Roth agrees: “So a child who worked their butt off and just has some issues, they’ll get the same grade as somebody a lot of times who didn’t turn anything in at all. What are we teaching them? What’s going to happen when you don’t turn your work in at work?”

Blair also served on the district’s Teacher Advisory Council last year but said she was disappointed when some of what they advocated for — including a change in the grading policy – wasn’t done.

“I mean, I think they [the concerns] got heard, but nothing ever happened, there was no follow-through. I think that’s probably one of the biggest reasons I left was the follow-through from those who make decisions or those who teachers and students need support from,” said Deen.

Grading and student accountability

At the February 1 Board of Education meeting, Assistant Superintendent of Support Services Julie Varnam presented on the 50% grading policy.

In her presentation, the district cited a 2015 policy brief: “The Unintended Consequences of Grading Practices”, that said, “Assigning zeros to students is a barrier to learning and if [sic] often non-recoverable. If a student receives a grade of zero on an assignment, it may take as many as nine scores of 100 to pull the average grade into the passing range.”

The district maintains that the current NHCS policy on grading “is intended to give students a chance to recover even if they fail an assignment or a grading period. Along with being mathematically unjust (a zero and perfect score average to still be a failing grade), a zero provides no information about what a student has learned. It is left as a distortion of the student’s overall performance.”

But Dr. Barnes said that because of concerns from former teachers like Roth and Deen — and the results of the December staff climate survey, the district has developed a task force to address grading policies.

“I want to make sure that before a decision gets made, you’ve had your opportunity to share your concerns with it. And so the more that we can do that, I think the better it will be. And that’s part of the reason for sort of this listening tour is to get out into the schools and make sure that voices are being heard,” said Barnes.

Erica Vevurka, director of K-12 education at the Hunt Institute, a non-profit, educational research and policy organization, said the school’s leadership has a strong impact on how well the teachers’ concerns are taken into account — which enhances the probability they will stay in the profession. She said state legislative leaders discussed this at the institute’s March educational policy retreat.

“We also had a conversation around rethinking educator work flexibility and around school climate, and how we can make work less stressful, such as rethinking the principal role for folks,” she said.

Vevurka said teachers won’t feel fully supported until administrators hear directly from them: “School leaders certainly can do so through anonymous surveys, having an open-door policy, and differentiating support between teachers and teachers have different needs.”

Another major concern for Roth and Deen was the lack of accountability in terms of student behavior— and even attendance.

“There’s a push not to do out-of-school suspensions, but then that leaves some students who make some really poor choices in the classroom who disrupt other students from learning. But when we don’t hold them to high expectations in their actual education or for them to actually come to school, it’s hard to hold them to high expectations for behavior and other areas as well,” said Deen.

Kim Roth sees it the same way: “They’re [the district] so worried about how many kids are going to the alternative school, how many people are suspended, how many people are graduating, that those things become meaningless. Because, you know, it doesn’t matter how many kids are suspended, if you’re simply not punishing anybody, the behaviors are worse.”

Compensation and advancement, demands on teachers

Ken MacGillivray was a high school chemistry teacher for 22 years. He left in 2019 — and now works for nCino.

He said he left because of the lack of leadership at central office and stagnant career advancement and wages. While the district now offers some of the highest salaries in the state, due to a county supplement last year, it’s still not keeping up with inflation.

“And so that is basically promising people that as things stand now unless there’s like zero inflation, or there’s deflation, that you’re going to have less buying power. Message received, I think that if you want folks to move along, or try something else, that would be the best way to do it,” said MacGillivray.

Vevurka said that in 2016, North Carolina launched the Advanced Teaching Roles program to provide teachers with increased compensation for those who are high performing, but for counties in the Cape Fear region, this grant isn’t available.

Dr. Barnes said he knows how important salary is but cites the work of scholar Daniel Pink in that, “financial compensation is one piece of a larger puzzle. And that what really affects employees’ job satisfaction is also the ability to gain mastery in your work, self-direct what you’re doing, and have a vision and a passion for a common purpose.”

Teachers who left, like Kim Roth and Blair Deen, said it wasn’t about the money. It was this purpose and value piece.

“Having just some general respect for the profession, and that’s from the top down, the legislators don’t respect us. The parents don’t respect us; the children don’t respect us. Our Board of Education, the majority of them don’t respect us. And the superintendent doesn’t respect us,” said Roth.

Roth said she also was upset with the number of demands put on teachers, like the push to individualize learning for students even though all students are accountable for the same end-of-year exam.

“And we’re getting mixed messages, it’s standardized tests, but differentiate. I’ve got a classroom with academically gifted kids, three kids who don’t speak English, kids on IEPs (individualized education plans) and 504s (behavior plans) all in the same class. How am I supposed to manage that? How am I supposed to do what needs to be done for each child? And why is each child taking the same test? They can’t do the same classwork. You got to change the classwork for them; how can you take the same test? And why is that test suddenly the ‘be all end all’ of everything?” said Roth.

Some of Roth’s concerns are being taken up by State Superintendent Catherine Truitt. In February, member station WFAE reported that Truitt is looking to change the accountability model for state public schools. This model mainly evaluates schools on an A-to-F model based on student performance on end-of-year state tests in reading, math, and science.

Dr. Barnes said the district is trying to help alleviate concerns so teachers feel that they can stay in the job — because they want to retain the teachers who are best for students.

“I would say, of course, that if someone is running into a situation that they are having difficulty handling or need even a place to process – HR is a place that supports all of our employees. And I would encourage folks to reach out. We get emails every day, and if we can guide folks and support folks, that’s our job,” said Barnes.

But to keep more teachers in the classroom, Kim Roth said, it might take more of a paradigm shift in education: “They misinterpret who the customer is. The customer isn’t really the family; it’s society as a whole, I think. And it’s a very important, a very important customer, you can’t do exactly what each parent wants to be done, you know, you have to look at society as a whole.”

Bittersweet goodbyes

While Blair Deen, Kim Roth, and Ken MacGillivray all said they are enjoying their new careers, leaving teaching was no easy feat.

“The tough thing is to leave behind the thing that’s the most fun, and what’s different, and what’s exciting is every single day is meeting the students and interacting with the parents, working towards those shared goals,” said MacGillivray.

For Roth, it was the support of her colleagues and learning along with kids: “Honestly, I enjoyed the students and enjoy the kind of interpersonal contact, enjoyed the teaching, and the fact that it was never the same any day.”

When Deen announced her departure on Facebook on January 5th, she wrote, “Walking out of this room today is hard and easy, all at the same time. I will deeply miss my students and seeing them learn!”

“Wow, that might make me cry. That was a hard day. I loved teaching. I loved my students. And I loved what I taught. And I saw value and importance in it. And so it was hard to walk out of that room, knowing that I had put so much into it. And so many of my students had gotten so much out of it over the years. Yet, it was easy. I was walking into an awesome job; there are so many opportunities out there right now,” said Deen.

Deen said that even though she’s out of the classroom, she hopes to become an advocate for public education and wants to be an industry partner for students studying interior design.